September 10th, 2020

Citizen-led Data Governance

This article is the third in a series and forms a core area of research carried out by Aapti Institute’s Data Economy Lab. As part of this study, models from four cities (London, Seattle, Los Angeles and Barcelona) were selected and analyzed to understand how data sharing in cities is currently carried out. These models represent innovative mechanisms for how data may be effectively shared and are critical to consider for their respective strengths. Through this series, we also explore opportunities for data stewardship and how this framework may be useful in solving issues like a lack of accountability and transparency. Stewardship may also enable better control over data and safeguard privacy rights.

Part 3: Barcelona

Unique in its approach, Barcelona’s collection, use and governance of data provides important lessons on how the notion of a ‘smart-city’ can be reconceptualized to be responsible, citizen-centric and privacy-preserving. In order for cities to adapt and learn from these practices, the Barcelona City Council has also released ‘Ethical Digital Standards’: a Policy Toolkit for Cities.

These approaches have been guided by an overarching policy that was put in place under Ada Colau’s mayorship in 2015, which in part rests on the City of Barcelona’s Digital City Roadmap: Towards Technological Sovereignty.

This article outlines the DECODE initiative and briefly covers the city’s Data Commons Program. These initiatives enable social and community rights to data through different mechanisms.

Decentralized Citizens Owned Data Ecosystem (DECODE)

Barcelona was one of the pilot cities of the Decentralised Citizens Owned Data Ecosystem (DECODE) initiative, part of the EU’s Horizon 2020 program. Guided by the concept of a ‘data commons’, the goal of the project was to create decentralized technical infrastructures that enable citizen-generated data to be made available to a range of stakeholders — governments, innovators, researchers and citizens — through a model that grants citizens greater control over how data is used and who it is shared with.

What does this mean in the context of data stewardship?

A data steward acts as a neutral intermediary which facilitates responsible data capture and sharing often on terms of pre-negotiated user consent and governance. The role of this entity, therefore, is both to ensure data is governed in a secure way to safeguard users’ privacy, while also unlocking data from public/private stakeholders for greater social good. While the design and form of stewards differ based on data type and use-case, one of the potential benefits that can be enjoyed as a result of this governance model is the opportunity for greater individual or community control of data. In the context of Barcelona’s DECODE pilots and the city’s broader vision of a Data Commons, this is made possible through a host of open-source technology platforms, tools and mechanisms, which help the users actively participate, share and engage in the process of forming data governance policies and capturing data. It further grants citizens significant agency in determining under what conditions their personal data should be shared. This case demonstrates the framework of stewardship in practice, where the city of Barcelona acts a custodian for their citizens’ digital rights, but above all, citizens are equipped through technology to steward their own data for personal or community good.

How is data collected, shared and governed through DECODE?

As a part of DECODE, two different pilots were carried out in Barcelona:

- Citizen Science Data Governance (IoT): Enabling Social and Communal Rights to Data

The first pilot associated with DECODE also falls under an international project funded by the European Commission, Collective Awareness Platforms for Sustainability and Social Innovation (CAPS). This was carried out in 9 cities across Europe. The project aimed to generate and test a participatory methodology that grants citizen greater agency in raising awareness and addressing pressing environmental issues like noise and air pollution. The Barcelona pilot ran from 2016–2017 in conjunction with Fab Lab Catalonia and enabled citizens and community champions to design methodologies, collect and share environmental data through sensors in their neighbourhoods. While customized to each cities requirements, pilots followed eight key phases: Scoping, Community Building, Planning, Sensing, Awareness, Action, Reflection and Legacy. These steps are relevant to consider emulating while shaping participatory and community-led data collection and sharing efforts.

As a critical first stage, ‘Scoping’ involved identifying who is in the community, shared areas of concern and stakeholders who would be necessary to involve. A diverse set of stakeholders with a range of skillsets were identified as community members which included designers, teachers, developers, economists and activists. This is followed by ‘Community Building’ where project governance and management policies are co-defined, and community members are actively recruited to be involved as ‘Community Champions’.

In the third ‘Planning’ phase, the community defines the criteria and design of data collection based on their collective goals. In Barcelona, this took place in Placa del Sol, where planning included using a Sensor Strategy tool that helped citizens identify where sensors would be placed, how data would be collected and at what intervals.

The ‘Sensing’ phase is where data collection actually occurs and is carried out by ‘Community Champions’, citizens actively involved in the process, and intermediary organizations. Booklets and operational manuals were created and disseminated to ensure sensing processes were followed uniformly. In Barcelona, this was further facilitated by the Smart Citizen Kit, an open-source sensing platform developed by Fab Lab Barcelona, which included both a kit of sensors that was accompanied by a mobile application.

After data is collected, the ‘Awareness’ phase involves exploring the implications of the data, through analysis and how it can be best visualized and acted upon by relevant stakeholders. This is also the point at which citizens have a comprehensive discussion around data ownership, storage, management and sharing policies. Guided by a Data Discussion Sheet, these policies are co-defined. Citizens consider questions about the accuracy of data and also surface potential privacy concerns. This phase also considers how this data can be made most accessible to data contributors, relevant stakeholders and other citizens — this often involves visualization through an open Data Dashboard.

Based on the understanding and insights from data, the Action phase relies on citizens defining a series of strategies of how this data can be actualized in-person through protests, demonstrations, visuals or through digital interventions for example. In Barcelona, this meant creating a public installation to raise awareness around noise pollution. Reflection involves assessing and evaluating the process, defining new courses of action for citizen sensing and compiling best practices. This appraisal can be carried out through the use of questionnaires. The final stage, Legacy, involves sharing the process, findings and outcomes of the work through online and offline mediums, to catalyse further interest and participation of potential community members.

The process of co-creation from design to evaluation ensures high citizen participation and creates a sense of ownership over the data collection and governance process. Moreover, the crowdsourcing approach to data collection was successful in mobilizing a significant part of the community and raising significant awareness around issues of air and noise pollution. This prompted Council Members to take action to mitigate these issues by considering how Placa del Sol could be better used to minimize noise.

This example showcases that participation must be treated as a core tenet of stewardship and demonstrates how this may be implemented throughout the life-cycle of the data collection and governance process.

2. DECIDIM: Collective Intelligence for Democracy

Decidim, which translates to ‘We decide’ in Catalan, is a participatory platform for democracy that was funded and built by the Barcelona City Council. Building on the foundation of this existing platform, DECODE partnered with Decidim to pilot technical measures that enable verified citizen participation. As a platform, Decidim facilitates citizen engagement with the government, where through the platform individuals can consult, contribute to policy proposals, sign petitions and participate in initiatives like budgeting. It also supports organizations and associations to self-organize and assemble online.

As part of the DECODE pilot, these functions were enhanced to be more secure, auditable, reliable and anonymous. In addition, data that citizens choose to contribute along with other data streams from the City Council are aggregated and visualized in the BarcelonaNow dashboard. This forms a part of the ‘Data Commons’ policy [4]. Based on similar principles and ‘rights preserving infrastructure’ to the IoT initiative, Decidim ensures that citizens are equipped as owners of their data with full control over how it is shared. It effectively places power in the citizen’s hands to be the custodians of their own data and in this sense, acts as a personal data store.

GOVERNANCE:

Based on principles of open collaboration and tech sovereignty, Decidim has three layers of governance: Legal, Code and Community. At a legal level, the platform and its contents are largely open-sourced. The code for its infrastructure is licensed under creative commons and hosted on GitHub Repositories that can be modified by registered users or Decidim Leaders. Given this open-source format, participation from the community is encouraged and a Code of Conduct ensures this takes place without harassment. The architecture and governance are open-sourced to ensure there is a high degree of transparency and traceability:

“With the exception of data that can affect user privacy, details of activities in participatory processes in digital media need to be absolutely traceable and public, if a new level of transparency in participation is to be fostered”.

Decidim was designed as a ‘multitenant platform’ which renders it to be used or installed by various institutions. This means it is relatively easy to be managed and maintained by a single entity and is highly scalable for adoption with small agencies or local authorities.

SAFEGUARDING PRIVACY THROUGH TECHNOLOGY:

Both DECODE pilots employ the concept of privacy by design, where safeguards are baked into the technical architecture of the systems in order to maintain compliance with GDPR and in some cases, provide concrete strategies that protect users rights beyond these requirements. This is achieved through a ‘privacy-aware architecture’ that allows for decentralized data governance.

For instance, citizens can leverage a set of Smart Contracts and related Rules that outline what data (Personal/Non-personal) can be shared, under what conditions and with whom. These smart rules are encoded through a set of algorithmic protocols but can be activated by citizens through a simple plain text form. These are cryptographic techniques which rely on a ‘Zenroom’, a cryptographic system which implements a Coconut credential scheme. The ZenCode gives citizens without any coding expertise, but minimal training the ability to encode the rules that form the basis of the Smart Contracts.

Smart rules are also strengthened by virtue of the blockchain or distributed technology upon which they rest. The ledger remains highly secure due to the usage of ‘Attribute-Based Credentials’ (ABC) which maintains compliance with access controls defined by the users through the Smart rules interface.

For Decidim, ABC combined with other cryptographic techniques offers citizens the ability to sign petitions, raise issues anonymously, without sharing personal data, while ensuring their identities are verified. This fuels active citizen engagement through the platform, without fear of retribution from the state or political parties. It also allows citizens to selectively share necessary information to verify aspects like their age. For instance, for some initiatives on Decidim, the platform must verify whether citizens are above the age of 18 and residents of the city. Through Smart Contracts, only a portion of their personal information is securely shared to verify this in order that they can proceed in using the service.

As a model of data sharing, DECODE has a number of strengths as it:

Grants users greater decision-making power over data use and sharing: powered by blockchain technology and an access based credential system, citizens are able to assign ‘Smart rules’ that function as licenses to dictate how their personal data may be used and by which stakeholders.

Operationalizes civic participation and governance around data collection: Recognizes citizens as active actors in data collection processes, an initiative called ‘Making Sense’, and empowers local residents to crowdsource and make use of data from their locality. Citizens are also given the option of visualizing this data on BCNow or sharing it data with local departments and agencies through Decidim.

Creates platforms to engage, access and innovate using data: Through a civic engagement portal called Decidim, Barcelona citizens have the ability to share their personal data in order that the city can harness its public value.

DATA COMMONS PROGRAM

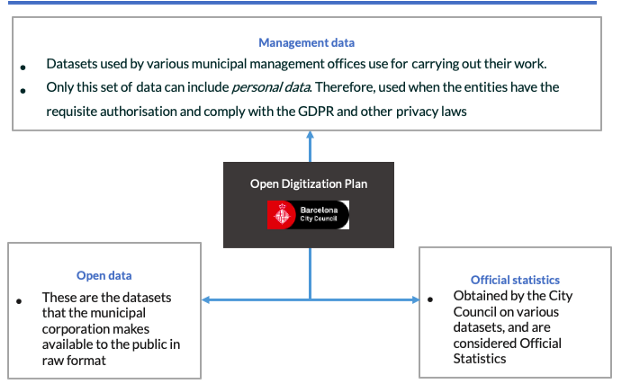

Based on DECODE, the Barcelona City Council also has instituted a Data Commons Program which values various forms of management data, open data, official statistics (pictured in the figure below) and potential external data as infrastructure and as a result posits it should be under democratic control.

One of the key pathways to operationalize this was to make public procurement for new software development or technology more transparent, simple and objective. The program also requires that 70% of investments must be for free and open-source software in municipal systems. This seeks to incentivize responsible innovation and technology from SME’s that aim to uphold citizen’s digital rights.

“publicly funded technologies delivering a public good should be transparent and open to public scrutiny.”

Figure 1: Different sources of ‘Data Infrastructure’

GOVERNANCE

In order to ensure transparency and accountability of data governance processes, Barcelona City Council created a Municipal Data Office (MDO) which maintains compliance with GDPR, is led by the Chief Digital Officer and supervised by a Data Protection Officer. The Data Office’s role is to govern and analyse data and coordinate its management in different areas and districts in Barcelona.

One of the main goals of the MDO is to unlock data of social or public value through the ecosystem by negotiating and arriving at data-sharing agreements with stakeholders. For example, MDO engaged in dialogue with a telecom company for over a year in order to access anonymized and aggregated mobility data. This data provided insights to better map the mobility of people in a precise way that could serve as a basis for better transport strategies.

This model is useful to consider for a number of reasons:

These initiatives indicate that there is a growing interest from citizens to play a more active role in data collection and sharing processes. Moreover, it is evident through the Data Common’s model that there is inherent value in unlocking data for the public good — whether it is to better map noise pollution levels or assess the quality of the air, where citizen-derived insights were subsequently translated into policy or political action.

In Barcelona’s case, these initiatives were largely successful as they were supported by a combination of EU level policy as well as political willingness and leadership domestically. However, this model is a testament to the relevance of data stewardship in redefining how data can be securely shared in a citizen-centric and privacy-preserving manner.

These practices can similarly be implemented considering the role of a steward, an intermediary entity who would leverage a range of technical and governance mechanisms to provide citizens with greater agency over their data.