June 7th, 2022

When the Data Economy Lab was established in 2019, our vision was to map the landscape of stewardship, delineate its various operative models and document practices of existing stewards or steward-like initiatives across the globe. Our report furnished a common taxonomy to unify the vocabulary around data stewardship and presented a classification framework that built on an analysis of existing use cases of stewards. A key area of inquiry for our research has been the sustainability and scalability of these entities. To this end, our paper on the ‘Principles for Revenue Models of Data Stewardship’ helped frame our initial thinking around incentive structures and related business models and guided further research around these entities.

While our research has highlighted the existence of several organisations or initiatives pushing for a more fair and just data economy, it has also become clear that not all of them have been able to survive the test of time. This has prompted a retrospective analysis of the stewards we had previously studied to understand their status – are they still operational? What are their business models? How have they managed to incentivise the participation of individuals, communities or other end-users? Have some stewards pivoted in focus or approach in response to an external trigger from the legal or policy environment? What has contributed to the growth of some stewards and the dissolution of others? Is this a function of funding, demand or capacity?

This blog attempts to tackle a few of these questions and provide a snapshot of the ecosystem at present – three years since we kickstarted the Data Economy Lab’s research on data stewardship. To this end, we’ve looked back at the 70+ stewarding entities to understand how they have sustained or scaled by building partnerships, securing funding, incentivised use of their services and/or expanding their teams. Drawing from our insights, we’ve highlighted common patterns and trends we’re seeing in the stewardship space.

These findings will feed into the research we’ve charted for the next phase of our research at the Data Economy Lab. Going forward, we will continue to identify barriers as well as enablers for stewardship. This will require unpacking the technical, social and financial levers required to create a thriving ecosystem for stewards and other stakeholders to co-exist.

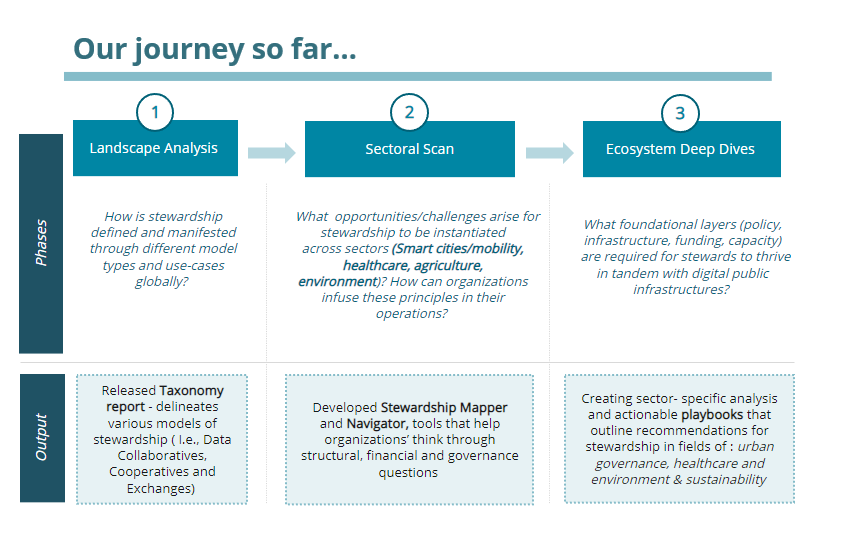

Data Economy Lab’s journey since 2019 to build a responsible and safe digital world

Methodology

We started by updating our existing database of 70+ stewards to include details on their operational status to establish if the steward continues to remain active. This database contains a long list of stewarding entities which operate across 4 sectors – environment and sustainability, healthcare, consumer welfare, and mobility and smart cities. Their operational status was examined through metrics such as their publications, collaborations with partners, funding models and legal status. Lastly, the metrics also helped us glean how certain entities have persisted through the years and functioned as scalable models.

Limitations

The status of these models was determined through pre-existing data and secondary research which may not always be reflective of the actual picture on the ground or sufficient in deriving the full picture of a steward’s activities. Where stewards were found to not be functional, it was not possible to identify the cause or experience that led to this outcome – which may be further explored in the future through carrying out in-depth interviews. Further, the sample size is in itself limited and primarily draws from the Data Economy Lab’s network of actors in the stewardship landscape.

Result and analysis

Common trends in the stewardship landscape

- Stewarding entities in the health sector are particularly resilient

It has emerged that stewards in the health sector are particularly resilient, with only 1 of 24 (4%) entities examined which are no longer operational. On the other hand, 33% of entities in the environment and sustainability sector (3 out of 9) are currently inactive, with corresponding figures for mobility and consumer welfare sectors standing at 23% ( 3 out of 13) and 18% (5 out of 27) respectively. This could be attributed to the pandemic which saw an increase in demand for digital health solutions that consequently led stewarding entities to establish several continuous partnerships with healthcare management companies, and data providers and successfully incentivised the participation of citizens to contribute their data. On the whole, 58 of 72 stewards considered continuing to remain operational since they were first examined as part of DEL’s research in 2019. - Blockchain technology is a means to enable individual ownership of data

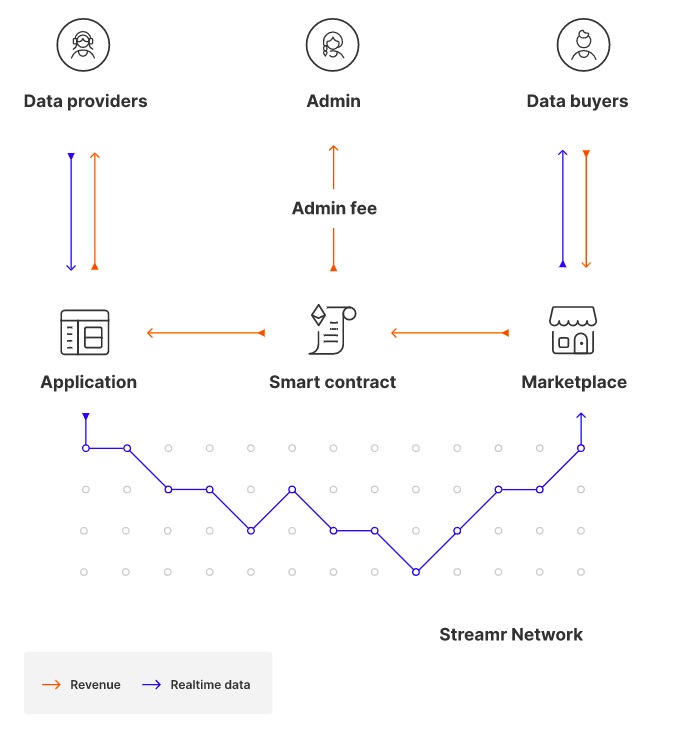

Stewarding entities like Geens, and BurstIQ reflect the trend of applying decentralised technology solutions such as blockchain to enable individuals to exercise control over their data. Decentralised web3.0 claims to solve existing issues with data ownership by offering both sovereign data ownership and social/ trusted ownership. ‘Data Unions DAO’ is an interesting scalable marketplace for data which is community-owned and controlled. Data Unions allow individual users to join the organisation through smart contracts and aggregate data and monetise the same in a controlled manner with the ability to vote on how and where data is used through an explicit DAO governance protocol. DAO organisations like Streamr and Swash offer Data Unions as their products. However, it remains to be seen how such blockchain-based solutions can build and sustain ‘data unions’ in the long run, as they would require a critical mass of users to generate data for sale. Additionally, these “decentralised” solutions seem to have a limited focus on matters relating to governance, participation and representation within the structure of a ‘data union’ – foundational qualities of unions in the offline world.

Structure of a typical data union’s data and payment flows (Source: dataunions.org)

- Data trusts remain largely esoteric with limited practical resonance and application

There has been growing interest in data trusts as a model for stewarding data. This could be observed, for instance, in the spike in inquiries about data trust on search engines worldwide over the past year. This can likely be attributed to the fact that data trusts have been positioned as promising governance models whose core functions include: institutional safeguards to manage data misuse, empowering individuals and communities and providing ethical, architectural and governance support for trustworthy processing of data.Of the 72 models documented in Aapti’s database, there exist only 2 data trusts – both of which have been disbanded since 2019. This includes Sidewalk Toronto’s Civic Data Trust and the ODI Wildlife Techhub data trust pilots. Consequently, the lack of experimentation and practical application around data trusts is a function of its unique legal status, with its genesis in common law trust frameworks and attendant fiduciary obligations attributed to trustees. As a result, data trusts have limited feasibility beyond common law jurisdictions due to varied political and legal histories of different countries that determine data rights afforded to citizens as well as their enforceability of trust laws within the country. Considering these challenges, it is imperative to look to other models of stewardship like cooperatives and collaboratives that have demonstrated greater potential for empowering communities through alternative mechanisms of equitable data governance that do not rely on common law trust frameworks. - Private sector initiatives tend to be more sustainable when compared to entities funded by the government

Most private sector initiatives tend to be more sustainable when compared to organisations that are funded by the government. Out of 12 data exchanges in the database that were funded largely by the government, 25% ceased to function. Our analysis revealed that of the 11 projects which have been disbanded, 60% of them were either funded by the government or multilateral organisations such as the UN and World Bank. - Most EU-based private sector initiatives generate revenue through subscription or membership models

Most private sector initiatives and cooperatives examined in this study (such as Geens/GebiedOnline/Schluss/Midata/PolyPoly) generate revenue by incentivising members to pay a small subscription fee for secure storage of and control over their data. All of these organisations are based in the EU – perhaps suggestive of an appetite for ordinary individuals to engage and avail the services of stewards. - The evolution of the policy landscape has meant that data stewards are now in focus

Innovative models cannot achieve their full potential if the landscape is lacking in mechanisms of accountability, robust data governance, advisory protocols and tangible pathways to enable community participation in data decisions. Emerging policy developments that serve as enablers to stewardship include the Data Governance Act by the European Union which refers to the role of intermediaries in the digital economy and how stewardship can channelise socially productive data use to benefit the public. Similarly, through the introduction of the consent manager (CM) framework in India, regulators are beginning to recognise the extractive digital economy and offer the CM framework as a means to uphold user agency and data rights.

Scalability and sustainability of models in the data stewardship landscape

- Some models have scaled due to partnerships with data providers, technology firms and local state agencies

The pandemic saw an over-reliance on digital health solutions that promise to overcome the bottlenecks of conventional health systems which were otherwise overwhelmed and unable to manage stresses created by COVID-19. In such a milieu, data intermediaries in the health sector have played a crucial role by stepping up investments in technology and capacity building through innovative partnerships and data sharing among public health, technology firms and healthcare providers. Redox is an interesting use case that provides data standardisation services through its unified protocol for electronic health records maintenance – bringing providers, insurers and patients under one framework. Saluscoop is a health data cooperative which facilitated citizen participation in health research as a part of its CO3 project, expanding the scope for collaborative health data governance.Collaboration with state agencies comes with immense potential for scalability for stewards given the availability of data that rests with public bodies. For instance, in 2022, Findata undertook a joint project with Finnish municipalities to use data compiled from data controllers to examine how cities can bridge gaps in the delivery of welfare services. The main advantage was that Findata could access and use data across diverse registers which helped provide a multifaceted perspective on the state of welfare services provided to families through analysis of their educational, income and health data. The Yale University Open Data Access (YODA) Project acts as a data intermediary to facilitate the sharing of clinical research data between members of academia, government, and private industry for meta-analyses, replicating trial results, building upon prior bindings, and conducting secondary analyses.Elsewhere, Strava Metro partners with public agencies such as Departments of Transportation, Metropolitan Planning Organisations, counties and cities like Sydney, Oslo and Sao Paulo to improve infrastructure for bicyclists and pedestrians.In India, the Foundation for Ecological Security which houses The Indian Observatory program brings together 1800+ disparate government and open datasets to create contextually-sensitive decision support tools on natural resource management. These examples are indicative of the need to foster greater engagement/collaboration between public sector agencies.

- Some models have rebuilt their business structures to improve product offering and financial sustainability

Certain stewards have restructured their business models to make their products and services more accessible and/or automated. For instance, Idaho Health Data Exchange underwent a significant revitalization of its business model and technology stack and service offering by partnering with Orion Health (provider of health management solutions). Subsequently, its migration to the Amadeus platform proved to be beneficial in enhancing value for patients. This is because Amadeus is a highly scalable and open platform whose API layer allows for 3rd party developers to build new capabilities, enabling the best health services applications to be developed while fostering innovation.Such use cases illustrate how data stewards need to forge creative business models that provide sustained sources of funding and revenue for themselves. Other examples that stand testament to this insight include Luna DNA whose governance model centres around recognizing the value of individuals’ data and compensating them for sharing genomic and health data for research. The Luna model ensures that users are provided agency over their data and are adequately compensated for its use, ultimately creating value for its members as well as revenue for itself. - Some models engage and empower communities as a way to unlock the societal value of data

Cooperatives like Drivers Seat import gig worker data and seek to help drivers harvest industry data and reclaim control over their data, furnishing a valuable precedent for community mobilisation and group enfranchisement around data. Gebied Online, another cooperative, seeks to impact greater control over members’ data and is driven to reinvest profit back for the benefit of the member community. Abalobi is a data cooperative that allows fishermen to collect data and negotiate the conditions and parties with which such data is shared, thereby increasing their bargaining power.Other examples of similar stewards include Variant Bio which works with historically marginalised populations to facilitate people-driven therapeutics. At Variant Bio, before the start of each research project, communities are consulted to determine the objectives of the study and ensure that their data is used within a framework that focalises community prerogatives.

Networks of solidarity in the stewardship ecosystem

The stewardship ecosystem has expanded since 2019, building communities of concern around equitable data governance. The stakeholders within this ecosystem seek to support each other along a few important pillars outlined below:

- Funding & mentoring support

Initiatives such as Mozilla Foundation’s Data Futures Lab provide a space to explore new approaches to data stewardship by providing funding and facilitating collaboration has onboarded four organisations – Place Trust, Driver’s Seat Cooperative, Drivers Coop and Digital Democracy as grantees. As part of this program, organisations receive $100,000 in funding and access to a network of experts to implement user-centric data governance policies. These projects will help pilot new models of stewardship and provide much-needed financial impetus within the ecosystem. Elsewhere, Open Data Manchester, another non-profit, has convened a working group on data cooperatives for stakeholders to connect and learn from each other. Zebras Unite is another data cooperative which connects its members and investors, which demonstrates the potential of democratic networks and infrastructure to raise capital. - Technology, infrastructure and capacity building support

Community-oriented tools like Mapeo built by Digital Democracy were designed to capture environmental data and evidence of human rights violations, and have received support and funding from organisations like the Open Data Institute (ODI), McGovern Foundation and Mozilla Foundation. The ODI is also lending technical assistance to Mapeo to build inclusive tech for indigenous communities and develop protocols for indigenous data sharing.PolyPoly, an open-source EU cooperative, is another ecosystem enabler which merits exploration. They are leveraging decentralised EDGE computing solutions to enable resource-saving, scalable and GDPR-compliance. The interaction between enterprise (which supports business interaction and creates products like EDGE solutions), cooperative (which connects individual users) and foundation (which deals with governance of members’ data) are mutually profitable and ensures secure data flow across its supply chain.Dasra in partnership with Bloomberg, Societal Platform, Stanford PACS and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation is hosting a series of initiatives under the Data for Good Exchange 2022 India. The aim is to empower organisations to create a data-driven impact for alleviating India’s most vulnerable communities. These initiatives include learning lab sessions to surface solutions capacity building on the ground and supporting NGOs with design grants. - Community mobilisation & participation

Ecosystem support can go a long way in empowering community-led stewards in the environment and sustainability domain. Indigenous communities have been guardians of traditional knowledge, but are seldom involved in the governance of data derived from and relating to them. In this context, the role of ecosystem enablers such as the ODI and ICES are pivotal to the journey of indigenous communities, as they begin to take reins over their data.Data for Black Lives (D4BL) invests in research and spreads awareness on how algorithms and other technologies have furthered the legacy of marginalisation and invisibilization of Black communities within mainstream science and technology discourse. D4BL’s policy working groups (that include lawyers, scientists and technical experts) are building frameworks that relate to data governance – and uniquely acknowledge how data and technologies amplify historic discrimination and systemic oppression. Open Humans is a non-profit funded by grants from Shuttleworth and Knight Foundation that has adopted a participatory approach to healthcare research where patients are involved in framing research questions and are consulted periodically. - Principle-building and inter-stakeholder collaboration

Global non-profit organisations like OMF and NUMO collaborate and act as ecosystem enablers. These multi-stakeholder and multi-domain networks bring together important players to help harmonise understandings about data governance, navigate diverse interests and incentives around data and in some cases also create common standards or guiding frameworks or principles. For instance, they help in launching privacy principles for mobility data to assess policy or technical decisions and their implications on privacy. OMF, an independent nonprofit, offers a collaborative environment for municipalities, civic nonprofits, corporate stakeholders, subject experts, and the public to work together to solve emerging transportation challenges that affect communities.Cities for Digital Rights, a network of cities committed to promoting digital rights in the urban context through city action, has a sandbox that aims to become a testing platform for innovative products and services, as well as to support the development of local ICT and entrepreneurial ecosystems and to generate data to scale up and export these products.

The way forward

Our retrospective scan has highlighted a few areas that must be further investigated. To start with, it is necessary to better understand the appetite for stewardship at an individual and community level. Early research conducted by Streamr Network and Swash illustrates how consumers are curious about the opportunity to take control of their data and money income help consumers understand the value of data. Demonstrating the possible use cases and more clearly showcasing the tangible value of data can be a pathway to engage consumers and may be useful in creating stickiness around products and services offered by data stewards. This is an important area to address as, without a critical mass of users, it is exceedingly difficult to scale and sustain many stewarding platforms.

One of the takeaways from our research is that users demonstrated an incentive to share and participate in data decision-making where they felt a personal resonance or alliance with particular issues (e.g contributing to climate action efforts or powering more inclusive research studies). In some cases, mobilisation around data and its governance has been propelled by a failure on behalf of governments in addressing data related injustices – stewards are therefore perceived as intermediaries that can facilitate collective action and solutions.

One of the roles that stewards often play is to make data accessible to diverse stakeholders, considering varying levels of data literacy and perceptions of its value – this necessitates building more inclusive data governance architectures based on stakeholder consultation and involvement. There is a need to develop both the social and technological infrastructures that can drive data accessibility. Participatory methodologies that foreground stakeholder consultations to identify concerns about data sharing and delineate data priorities can empower communities to be involved in data governance. While several steward-like initiatives are thriving across sectors and use-cases, our research shows that many face challenges in sustaining and scaling. Varying support from the ecosystem and regulatory systems, policy pathways and governance principles will be required for stewardship to gain more ground. Therefore, a sector-wise ecosystem diagnosis of the regulatory, infrastructure and funding models of these organisations is needed to unpack and understand each of them.