August 21st, 2020

Image sourced by unsplash.com

With emphasis increasingly being placed on data-driven decision making, data stewardship is gaining pace as a mechanism to unlock the potential benefits of data while safeguarding the rights of people. Given this aspiration of a more balanced, democratic mechanism for data governance, accountability is often identified as a key principle for data stewards. While accountability may be universally acknowledged as desirable, it is often difficult to define and implies different ideals based on context. For instance, accountability in the public sphere revolves around minimizing corruption, and in the arena of corporate accountability, it refers to the corporation being responsible to its stakeholders for the economic, social, and environmental impact of its activities. However, these ideas need not necessarily be shared in the sphere of data governance.

Generally speaking, accountability is defined as “the obligation of an individual or an organization (either in the public or the private sectors) to accept responsibility for their activities and to disclose them in a transparent manner. This includes the responsibility for decision-making processes, money, or other entrusted property”. A paper emphasizing the lack of a concrete definition of accountability in a humanitarian context, identified up to 16 concepts amongst the definitions, and narrowed down four themes -empowering aid recipients, being in an optimal position to do the greatest good, meeting expectations, and being liable. In the context of artificial intelligence (AI), accountability “includes an obligation to report, explain, or justify algorithmic decision-making as well as mitigate any negative social impacts or potential harms.”. In the context of data rights, accountability has traditionally been understood to mean ‘notice and consent’, however, an authoritative definition of accountability in data governance is not available.

Framing of accountability as merely informing the data principal and seeking their consent for the usage of their data is insufficient. Evolving beyond this traditional understanding, the concept of accountability in data governance has to grow to give individuals a larger say in how and for what purpose their data is being utilized. In this sense, the concept of accountability is broadened from the perspective of the data principal to give them larger control over modes of usage of their data and play a more active role in determining the purposes of the collection of their data. We look at the data principal as an actor looking to hold the entities dealing with their data (data requesters, data fiduciaries, data custodians, etc.) accountable to them. The data steward is perceived as an intermediary between the two that enables the data principal to exercise accountability.

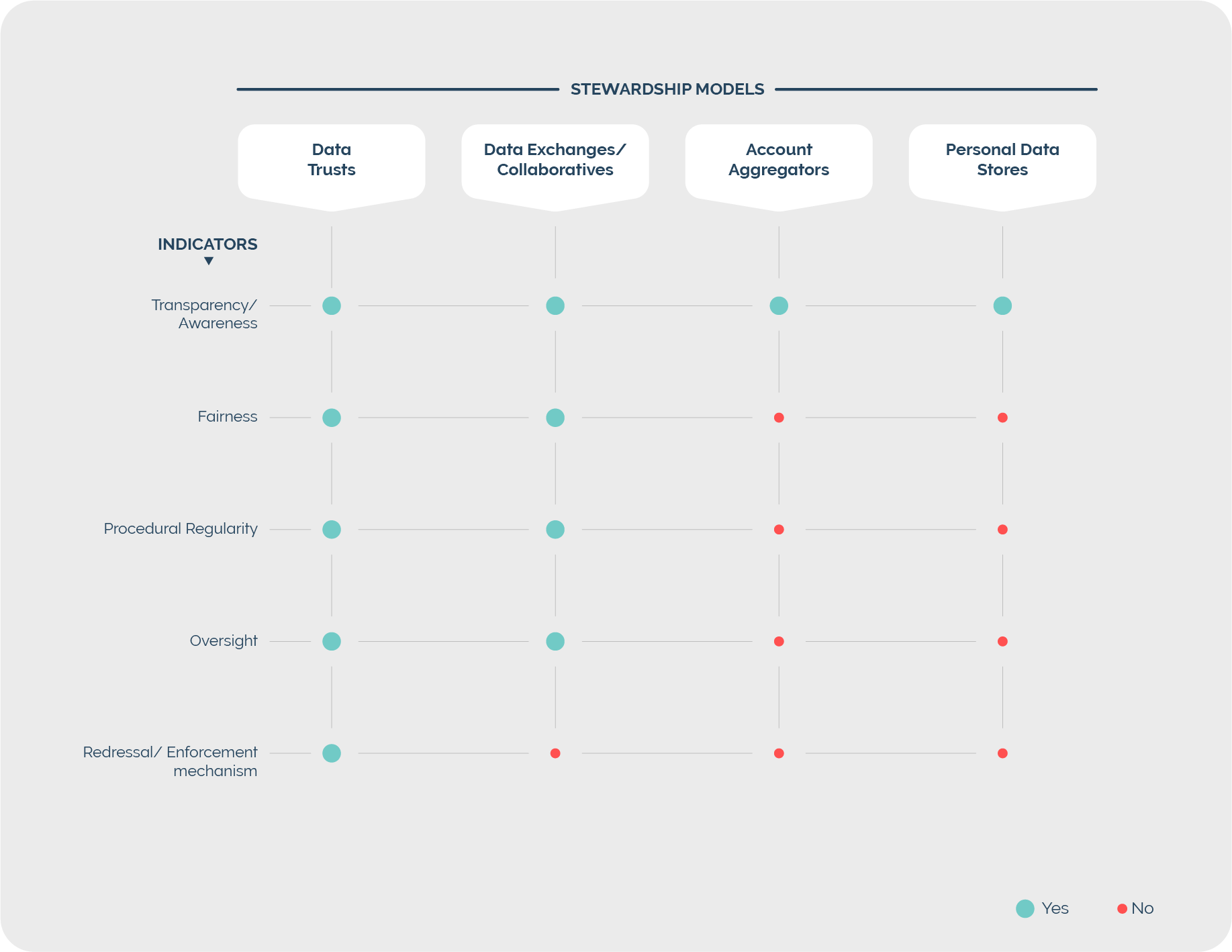

Different models of data stewards allow the data principal to exercise varying levels of accountability, thus, making them more comfortable with the notion of sharing their data. Drawing upon discussions and literature around artificial intelligence, we look at how a data steward could potentially empower the data principal to hold data requesters accountable, thus, enabling the sharing of data without hesitation –

- Transparency / Awareness – Most people are unaware of if and by whom their data is being collected. All models of data stewardship, by helping manage consent and access, make the data principal aware of the fact that their data is being cultivated and utilized and allow him to assert his approval or disapproval of the same by granting/withholding consent.

- Fairness – While it is no surprise that technology may be embedded with biases, a steward may minimize discrimination by the adoption of pre-processing methods while aggregating data. Instead of leaving the task of identifying embedded biases to the data requesters, the data principal can be empowered to assign this task to the data steward who is directly responsible and answerable to them. While a data trust and a data collective may be built in a manner that addresses inbuilt biases, no such possibility exists in account aggregators and PDSs as they are currently understood.

- Procedural regularity – A data steward could potentially act as an independent third party who could reaffirm whether the data requester is acting in consonance with the permissions provided by the data principal by conducting audits at regular intervals and overseeing mandatory disclosures by the data requesters. While the scope of a data trustee and a data collective could be broadened to include this responsibility, the design of account aggregators and PDSs itself precludes the inclusion of such responsibilities.

- Oversight – A data steward emerges as a single window for the data principal to manage and oversee the usage of their data and also revoke access to and correct their data. Through the steward, the data principal can be made aware of the different purposes for which their data has been utilized without being overwhelmed by the same. Data trusts and data collectives enable the data principals to play a large role in determining the purposes for which their data might be used and also give them access to their data as it is held by them (through their representative -the collective or the trustee). A personal data store (“PDS”) also empowers the data principal to self-regulate the usage and sharing of their data, however, the data is held by the PDS and involves processes that may be opaque, with or without options for revocation of access and correction of data. An account aggregator, by virtue of acting as a consent manager merely permits the data principal to either allow or disallow the use of their data.

- Redressal / Enforcement mechanism – We have delved into a multitude of ways in which the data steward could hold various third-parties accountable on behalf of the data principal, however, inextricably bound to this is also the concern of how accountable the data steward is to the data principal. Strong grievance redressal and enforcement mechanism to deal with cases of violation of the standard of care strengthens the trust between the steward and the data principal. As trusts are legally recognized entities and the safeguards in a trustor-trustee relationship stand codified, data trusts provide the strongest form of enforcement as any breach of trust may be prosecuted. The other forms of stewardship lack mention of such legally binding duties and responsibilities.

It is observed that all the stewardship models offer the power of exercising accountability to the data principal, albeit at varying levels and in different forms. In a sense, accountability is in-built in all data stewardship models. However, the adoption of certain measures by data stewards could enhance the trust that they enjoy among data principals. Data stewards can play a role in the creation of a culture of privacy across and inside organizations by formalizing the safeguards through contractual agreements with the third parties and companies who act as data requesters.

Through this, stewards can foster a larger accountability framework between all the concerned entities such as the steward, data requester, and data fiduciary. While the legal safeguards in the PDP Bill (Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019)and the NPD Report (Report by the Committee of Experts on Non-Personal Data Governance Framework)pertain to data custodians/fiduciaries, there is no mention of data requesters in other forms. Stewards or individuals (through their stewards) could be empowered to hold data requesters accountable through contractual agreements that delineate a specific grievance redressal mechanism and scope and mode of remediation in the event of a breach of the agreement.

That said, any potential breach of agreement is hard to discover. However, a legal mandate to conduct an annual audit of usage of the data, and share that with relevant stakeholders could enhance trust amongst the different entities and enable them to hold each other accountable to agreed-upon principles. It is undeniably in a data steward’s business interest to be accountable, transparent, and self-regulate.

It is opined that co-regulation combining both governmental regulation and self-regulation, the use of which has been endorsed in privacy governance, would also ensure greater accountability. An acknowledgment of ownership rights of individuals over their non-personal data as done in the NPD Report can form the basis of building regulatory mechanisms assuring accountability to the data principal. While a grievance redressal mechanism can be agreed upon by other means as explained above, an external enforcement mechanism would have to be led by a regulatory organization or a state agency.

This article was written by Preethi Sundararajan. Preethi is a second-year MA (Public Policy and Governance) student at the Azim Premji University. Her interests lie in governance issues pertaining to accountability/transparency and the financial sector, and the rule of law in India.